Dog Training with Positive vs Negative Reinforcement

🗓️ October 20, 2019 | 🕒 8 min read

Choosing a method of training is an important decision, which not only determines the efficiency of your training, but can also make or break your dog’s mental health. The terms “positive” and “negative” reinforcement are commonly used, but what do they actually mean? And which one is better? In this post we will explore these questions, and how our choice of training technique impacts both our dog, and the safety of ourselves and others.

What is positive and negative reinforcement? #

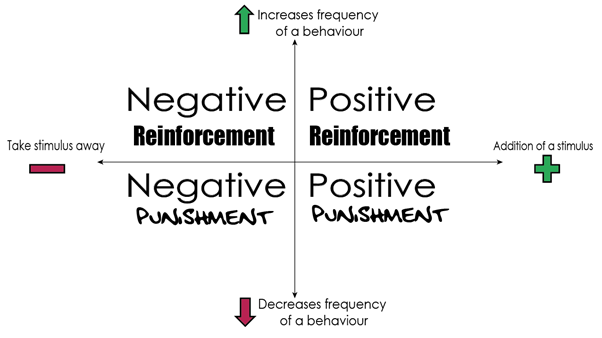

Animal training is based on their motivation seek out pleasurable events while avoiding unpleasant ones. First, let’s define some commonly used training terms. The term ‘reinforcement’ is used when a behaviour increases in frequency, while ‘punishment’ is used when the frequency of a behaviour is decreased. The term ‘positive’ refers to the application of a stimulus, whereas ‘negative’ refers to the subtraction of a stimulus.

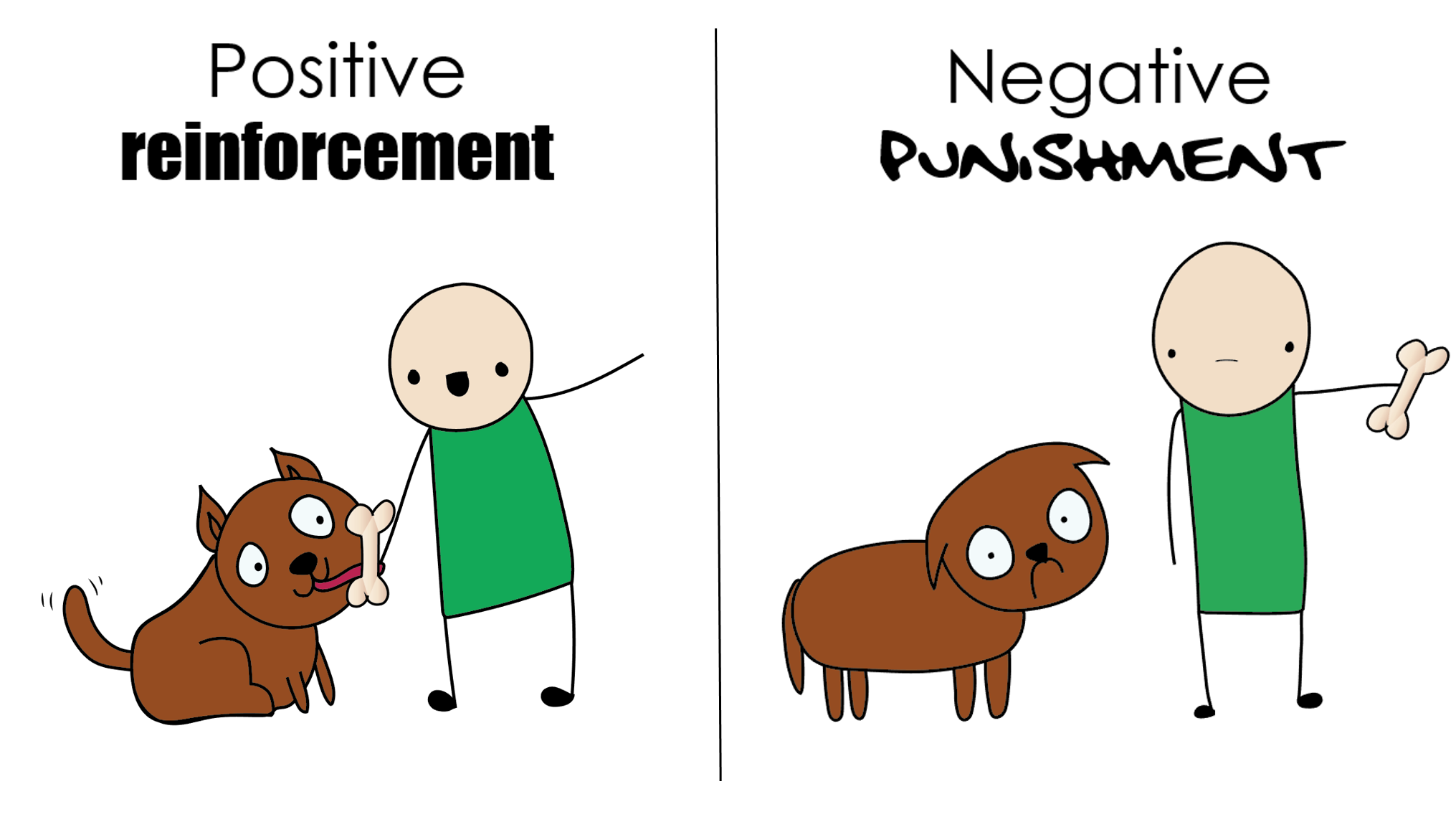

Since taking something bad (punishment) away inevitably coincides with applying a punishment in the first place (and vice-versa), we can conclude that negative reinforcement will co-occur with positive punishment, just as positive reinforcement will co-occur with negative punishment. For simplicity, we will lump these two methods together into: ‘reward-based’ and ‘aversive’ techniques. Let’s clear all this up with an example: If I were training a dog to sit using treats it would be positive reinforcement. Positive, because I’m adding a stimulus and reinforcement, because I’m increasing the likelihood of the dog sitting.

If the dog then stood up when I still wanted him to sit, I would use negative punishment by taking away the treat — negative because I’ve taken away the stimulus and punishment because it is likely to reduce the standing behaviour.

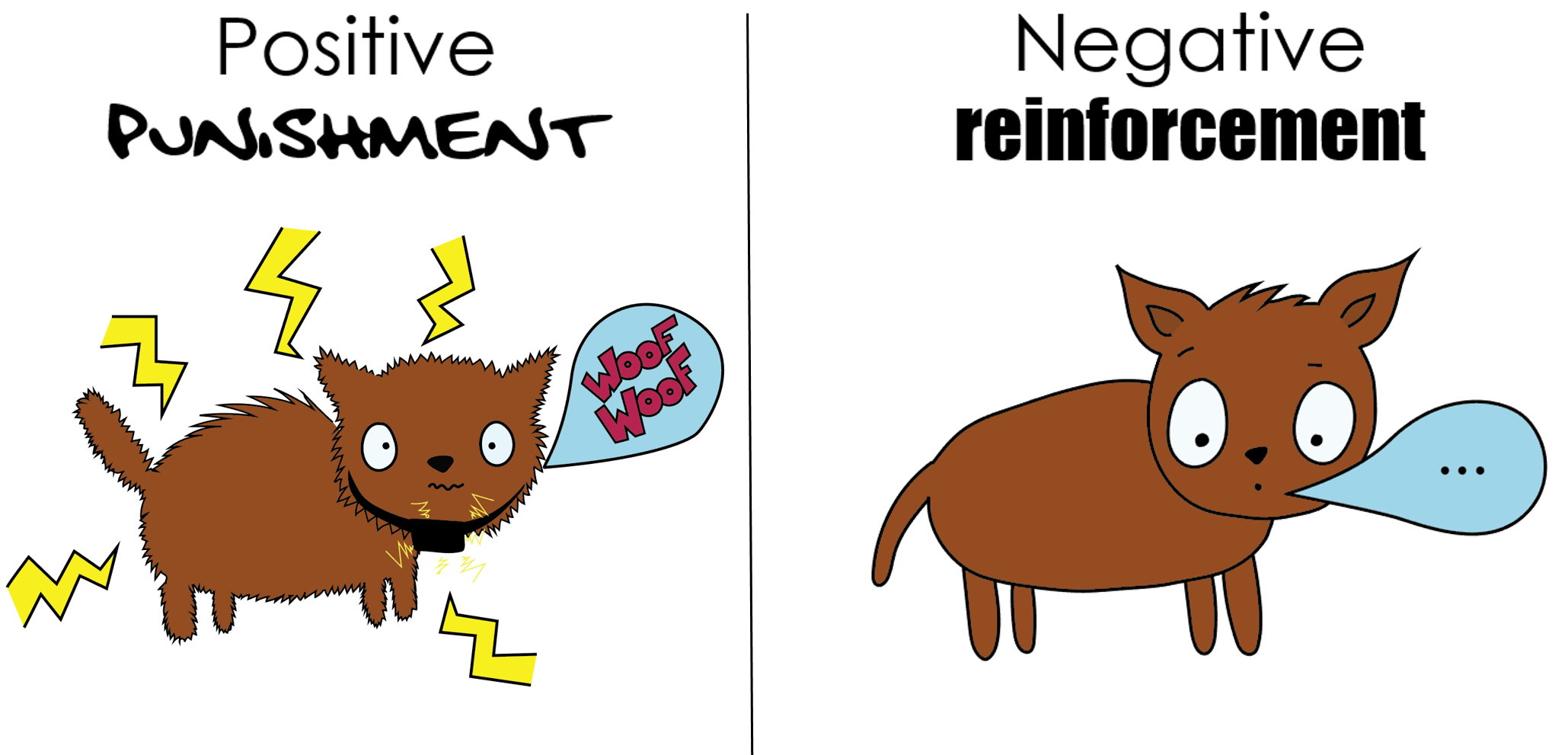

On the flip side, I could use an electric collar on a dog who barks. It’s positive punishment because we are adding a stimulus that is likely to decrease the dog’s barking.

When the barking stops, negative reinforcement is used, because the subtraction of the shock increases the likelihood of the dog remaining silent.

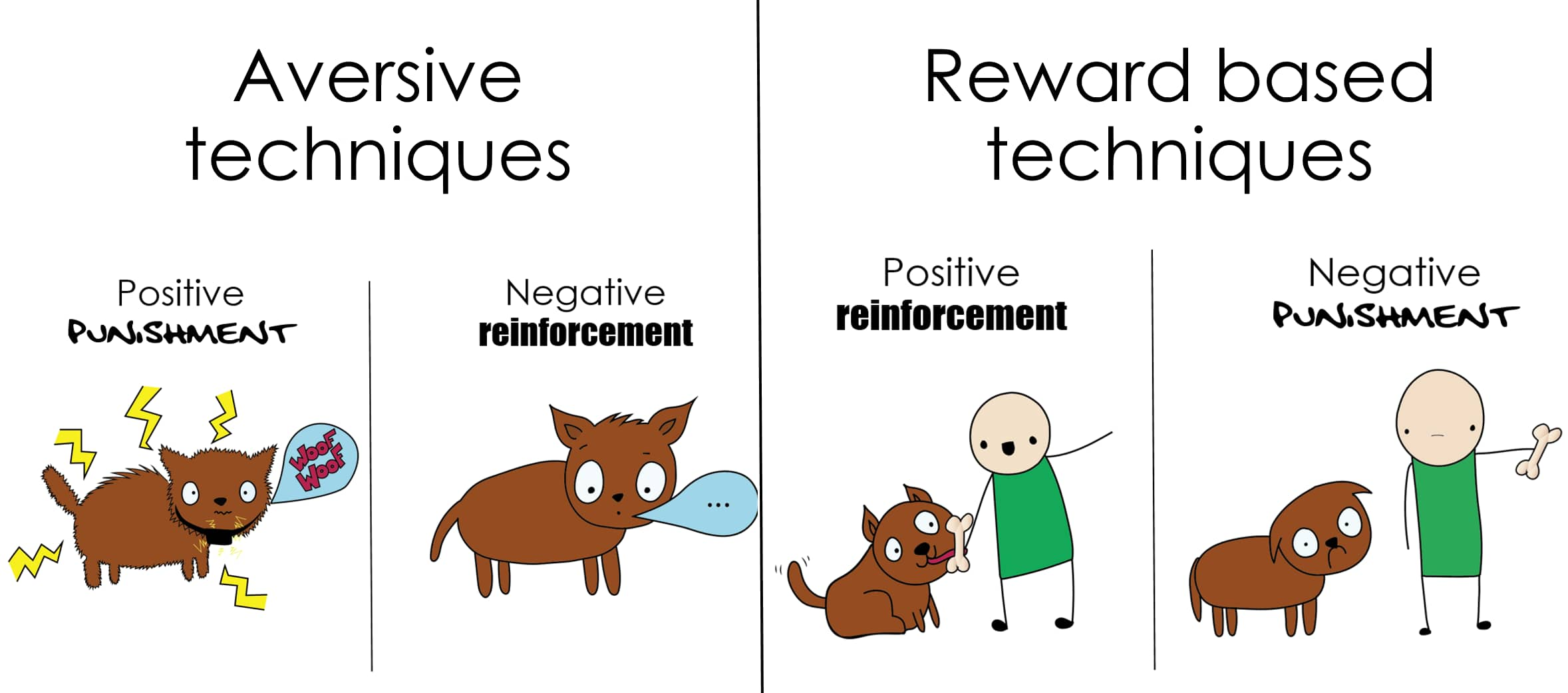

As you can see, whether positive or negative reinforcement is used, there is inevitably a punishment component. For the remainder of this post, I will instead refer to aversive and reward-based techniques.

Aversive techniques: involve the application or release of an unpleasant stimulus, to punish or reinforce a behaviour, respectively. (eg yelling, electric shock collars, choker collars, physical reprimand)

Reward-based techniques: reinforce a behaviour via applying a pleasurable stimulus. Behaviours are punished via the removal of a pleasurable stimulus.(eg treats, pats, toys, verbal praise)

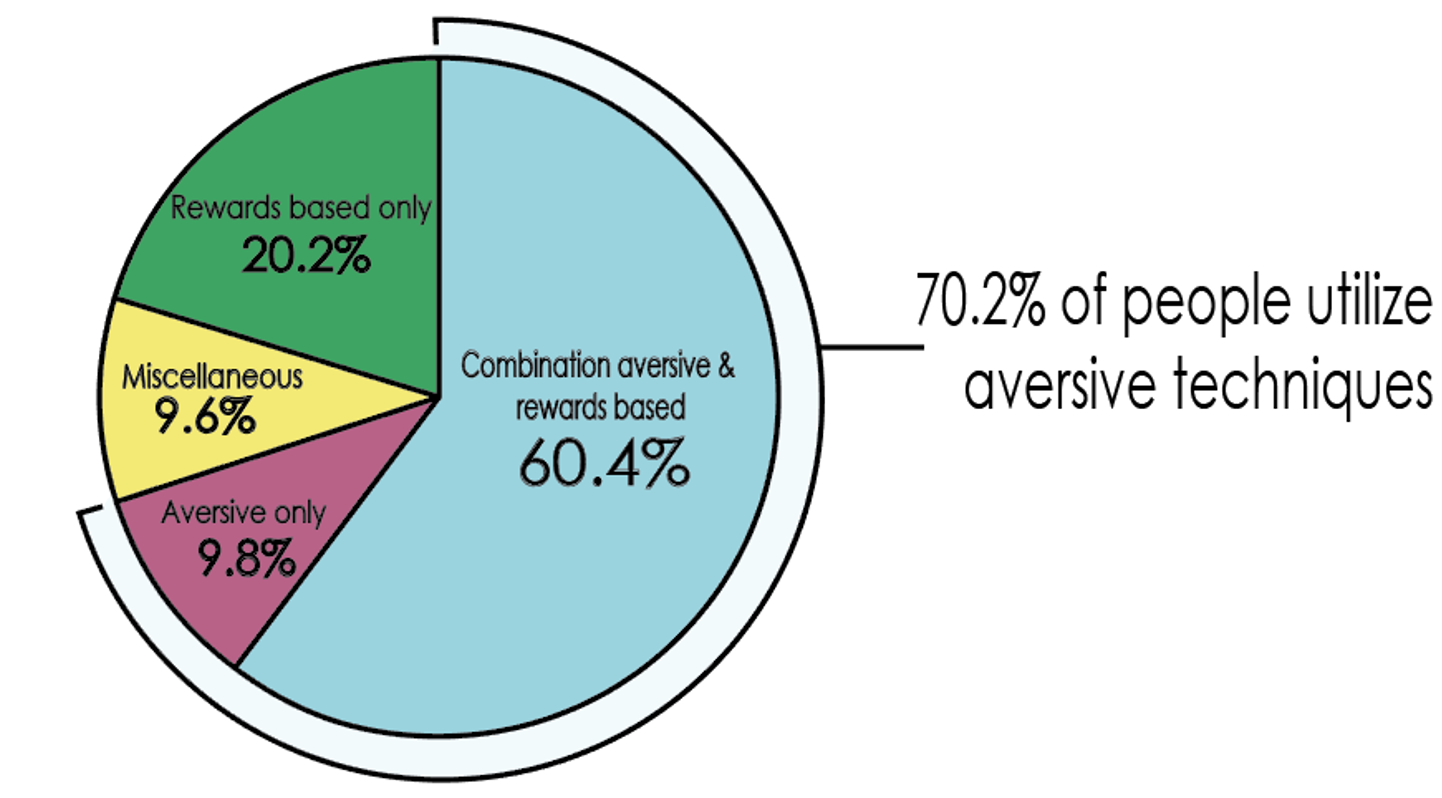

The use of aversive techniques is incredibly common within the pet owning community. A survey conducted in the UK found that 70% of owners incorporated aversive techniques into their training regime. Especially for punishing behaviours such as chewing or stealing objects.

Do aversive techniques work? #

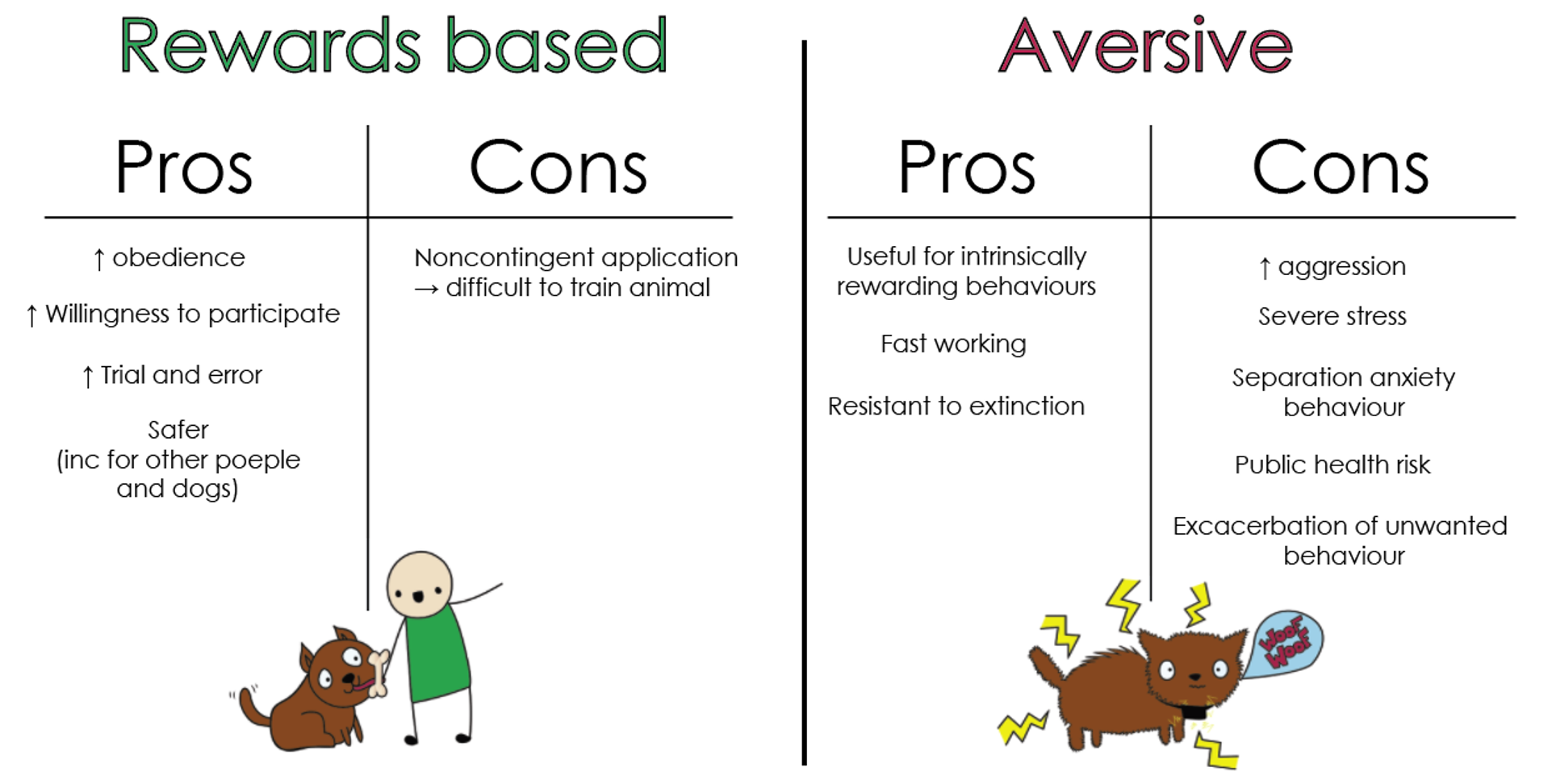

The simple answer is yes. Aversive techniques have been successfully utilised both in traditional dog training and in scientific studies. They have been shown to be fast working, resistant to extinction and may be useful when a behaviour is intrinsically rewarding, such as stealing food off the table.

However, for these techniques to be used successfully, the following points should be fulfilled:

- Perfect timing: it is imperative that the dog is able to irrefutably associate a specific behaviour to the application/removal of the aversive stimulus.

- Remote application: so the animal does not associate the aversive event with the human administrator.

- Antecedent signal: a warning signal before the aversive stimuli occurs should be used so the animal has the opportunity to avoid the stimulus altogether.

- Appropriate intensity: so the animal is sufficiently deterred from the behaviour, rather than building tolerance to the stimuli which results in a much harsher stimuli being required.

The correct application of aversive stimuli requires perfect timing, remote application, appropriate intensity and an antecedent signal.

That “perfect timing” point is an incredibly important one. Let’s have a look at what happens when the animal cannot make the link between its behaviour with the aversive stimuli…

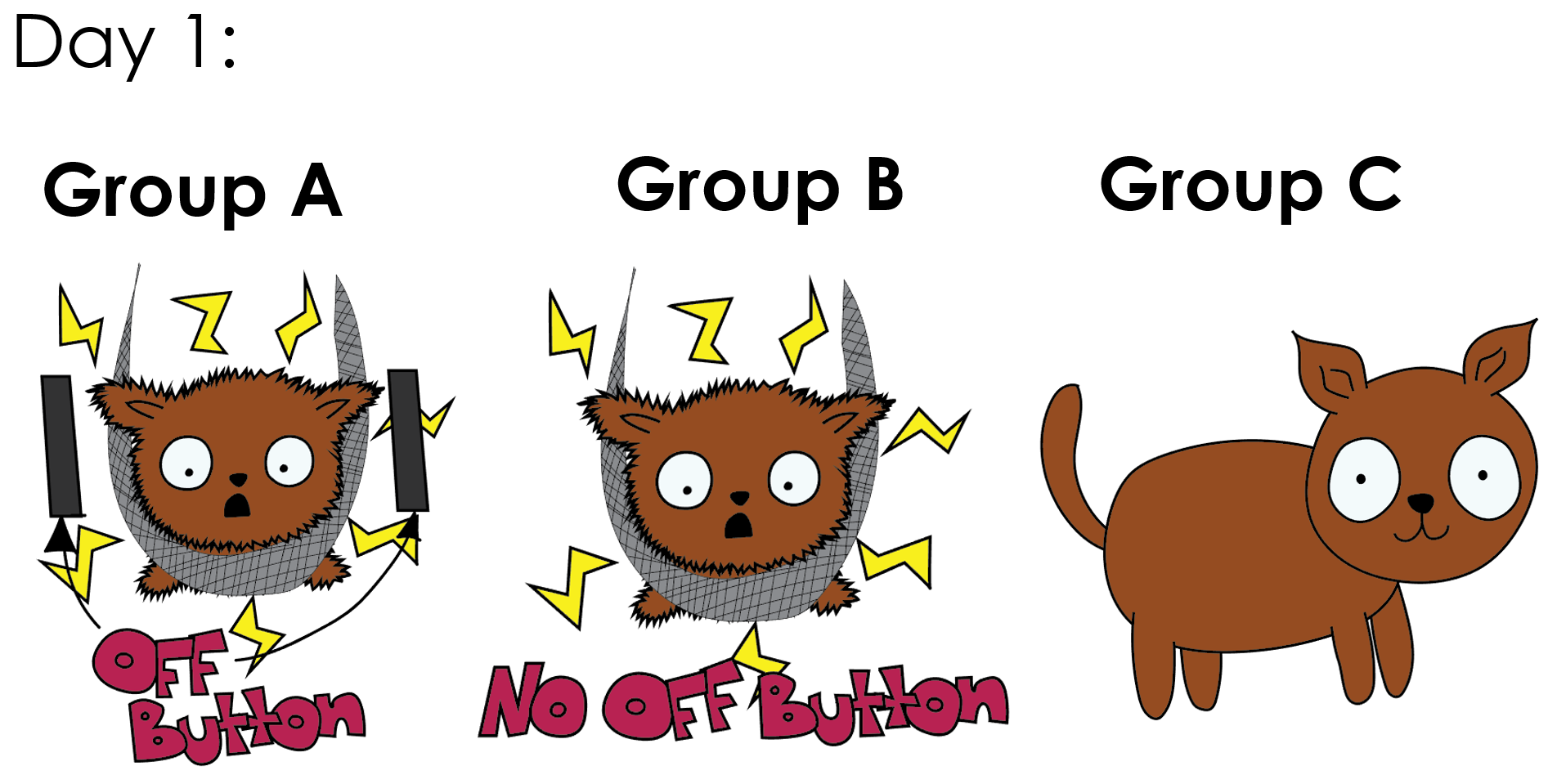

In 1967, a study was performed using 3 different groups of dogs. On day 1 of the study:

- Group A was restrained within a sling and subject to a continuous electric shock until they hit off buttons located beside their head.

- Group B was restrained within a sling and shocked continuously, but had no access to off buttons.

- Group C did not receive any shocks.

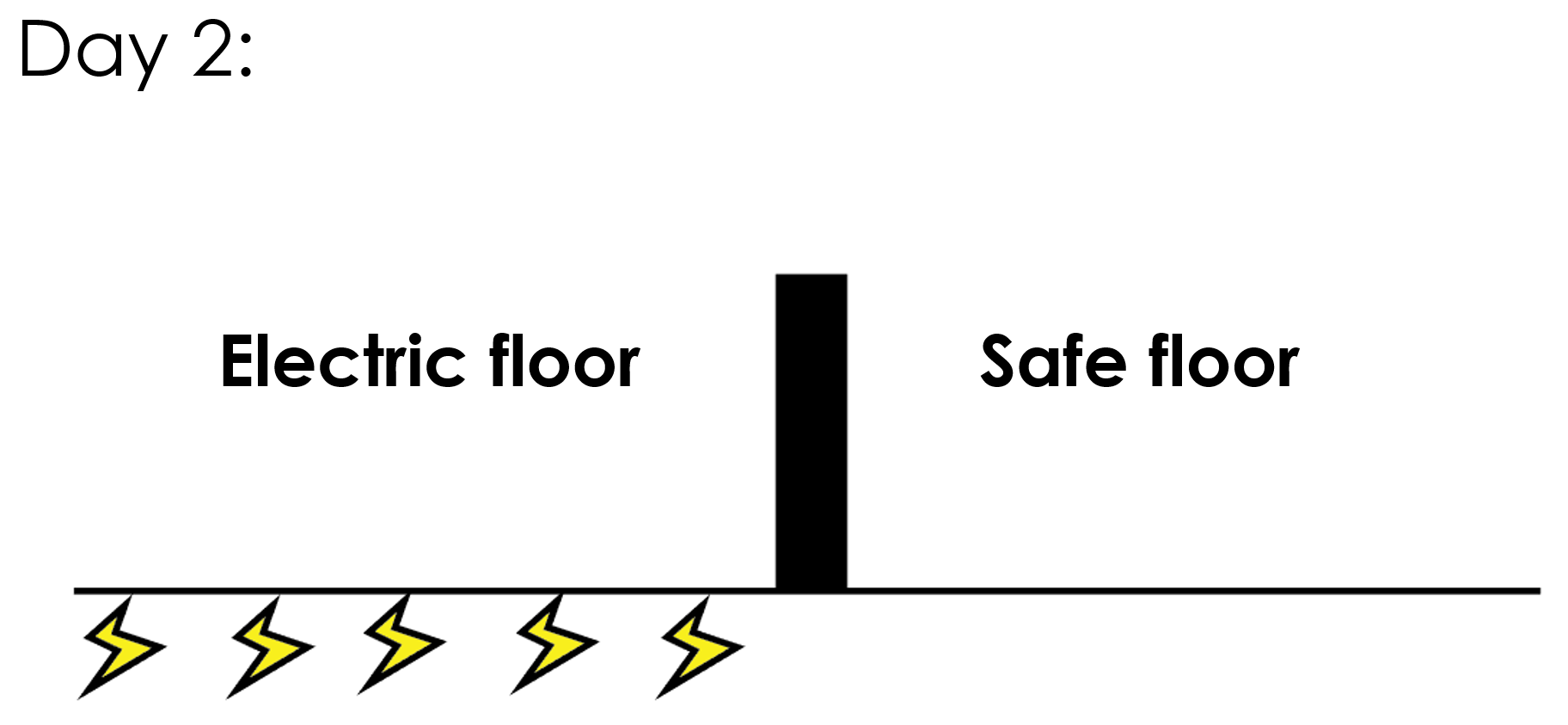

On day 2 of the experiment all 3 groups were subject to an electric floor. However, they were able to escape to a safe section if they jumped over a shoulder height barrier.

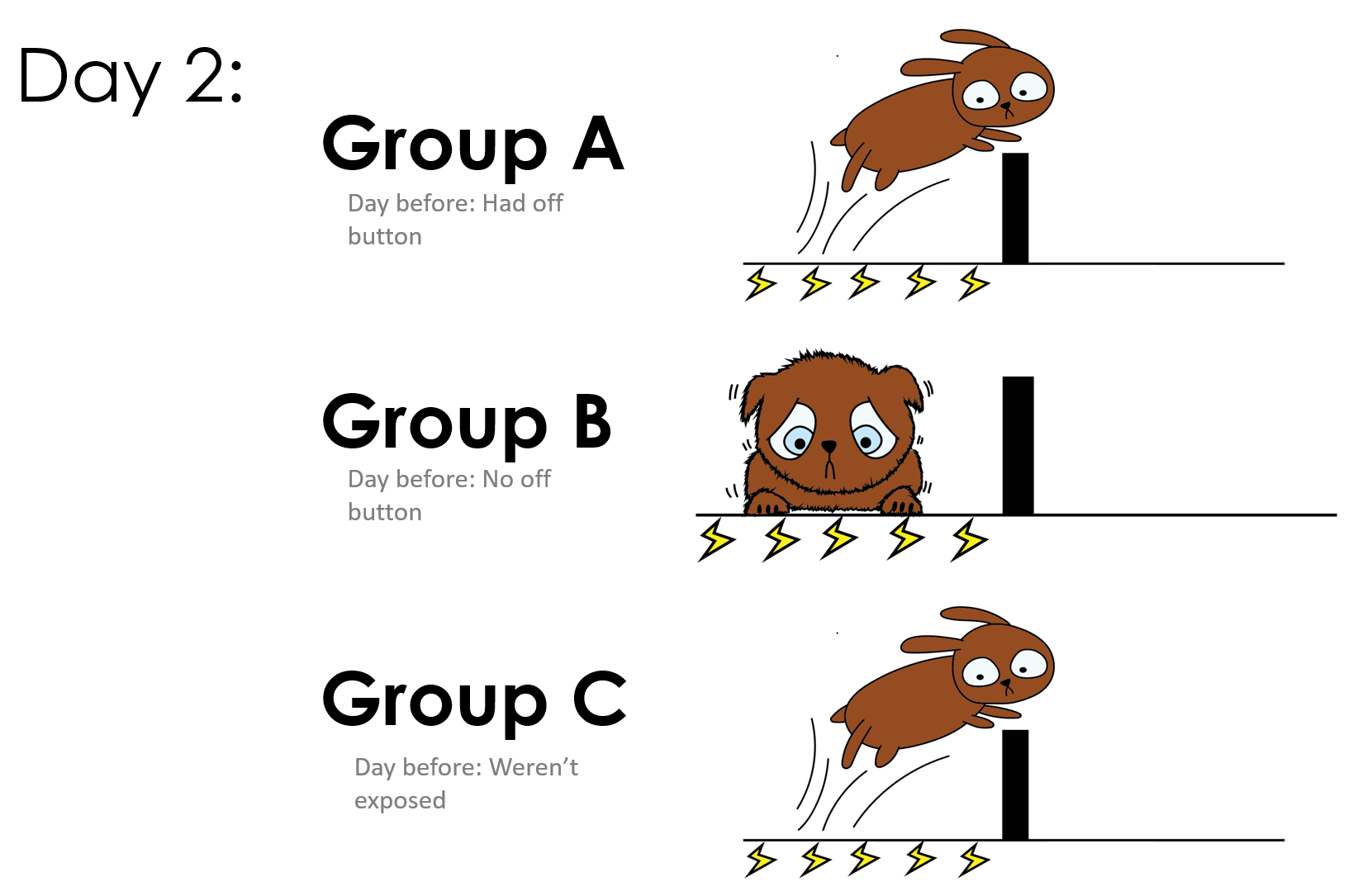

Group A and group C successfully jumped over the shoulder height barrier to escape the shocks. However, group B, the dogs that were exposed to uncontrollable shocks the day before, simply laid down and whimpered.

The behaviour displayed by the dogs in group B was labelled:

Learned helplessness occurs when one is subject to trauma they cannot control. The result is an animal that believes that it has no control over the events in its life and concedes. It has actually been used as a model for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and depression in humans.

So how does this relate to dog training? #

Studies have shown that owners tend to use aversive stimuli when emotions are involved and the timing is inaccurate, for example, yelling at a dog when you come home to find your favourite shoes have been chewed. This sort of application of aversive stimuli makes it extremely difficult for the dog to associate it with the unwanted behaviour. The dog might have chewed those shoes hours ago, and can’t figure out why they’re getting yelled at randomly.

I know that this is an obvious example of ambiguity, but you would be surprised at how ambiguous signals can be to a dog. For example, let’s have a look at electric collars (e-collars), which would theoretically, be the perfect aversive training method. They fulfil all the criteria seeing as they can be transmitted with exact timing, remotely applied, sound a warning signal and can be adjusted to an appropriate intensity.

Therefore, e-collars are an ideal model for extrapolating conclusions about aversive techniques in general. Although they can be transmitted with “perfect timing” by human reasoning, it is likely to be ambiguous to the dog. A study that involved shocking the dogs after they failed to come when called and shocking another group randomly produced the same cortisol (stress hormone) levels in both groups of dogs. Many other studies involving industry approved e-collar trainers have produced similar results. While it might be obvious to us why we are shocking the dog, the dog may be associating the shock to a stone on the ground or something else it has seen. This is a recipe for creating generally anxious dogs and risking learned helplessness.

If experienced trainers are struggling to apply e-collars correctly, what hope do we have? Especially with our other, inferior techniques like yelling etc.

On top of producing severe stress and risking the mental health of the animal, application of aversive techniques have been found to increase aggression, reduce playfulness and increase separation anxiety related behaviours. The aversive stimuli could be mistaken for encouragement, potentially exacerbating the behaviour. Furthermore, it poses a public health risk. Aversive methods more likely to trigger an aggressive reaction and with repetition dogs may learn to suppress warning signs, making future attacks difficult to predict and avoid.

Why you should practice reward-based training instead #

Reward-based techniques reinforce a behaviour by applying a pleasurable stimulus and behaviours are punished by removing a pleasurable stimulus. To date, there have been no studies where aversive techniques have demonstrated to be more effective than rewards based and many studies have concluded that reward-based methods are actually more effective.

Many studies have concluded that reward-based methods are more effective than aversive techniques.

This could be because the dog is more willing to participate in training or perhaps more confident in trial and error, increasing the likelihood of reaching the desired behaviour.

The only risk of non-contingently offering rewards is a lack of association between behaviour and the environment, thereby resulting in a difficult to train animal. For example, in one study food was randomly dropped into a rat’s cage while in another cage it was not. Later, a button that dispensed food was introduced to both cages. The group that randomly received food could not learn to press the button for food, whereas the other group of rats could. Essentially this is learned helplessness in reverse, more like “learned laziness”. The animal cannot associate its behaviours with good outcomes, believing good things will happen, regardless of how it behaves.

Weighing up the pros and cons of reward-based vs aversive techniques, we can see that reward-based techniques are the superior choice.

Reward-based methods are not only more effective, but don’t have a large number of serious risks. Before resorting to aversive techniques, all reward-based methods should be exhausted. If aversive methods do need to be used, it is imperative they are used correctly.